Jean-Baptiste Maitre (b. 1978)

Not Necessarily Words

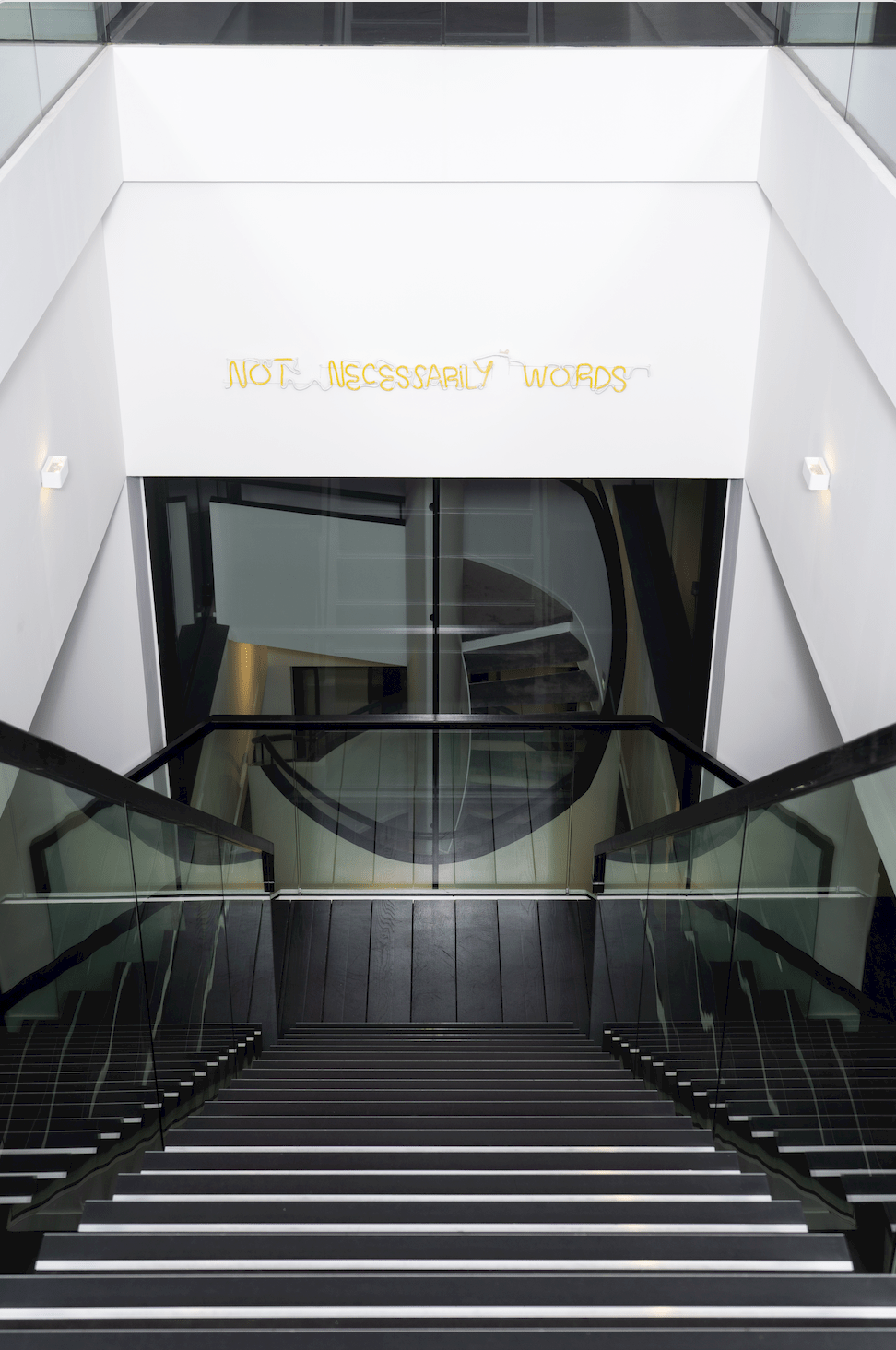

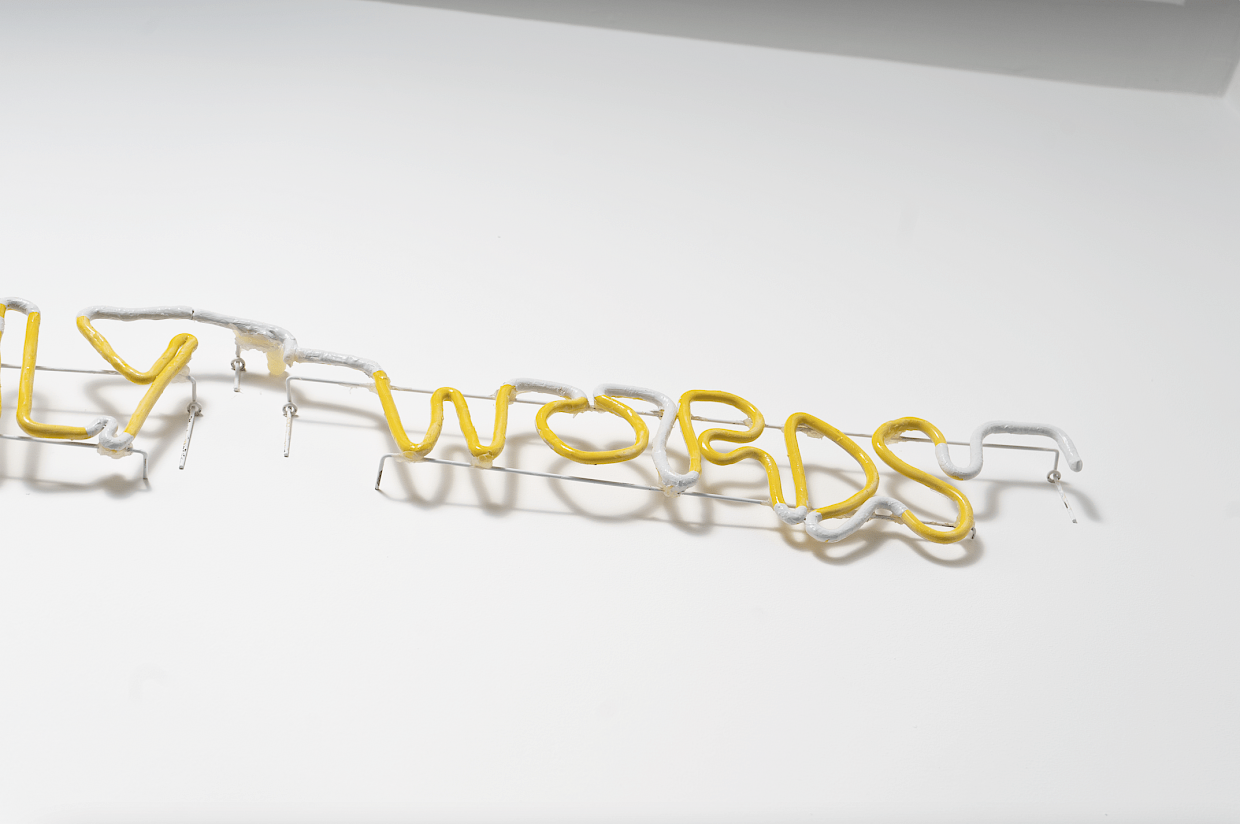

Not Necessarily Words was the title of Jean-Baptiste Maitre’s first solo exhibition at his Amsterdam gallery Martin van Zomeren. The underlying idea is that thoughts are more important than words. The art committee found the artwork to be suitable for a large law firm where the power of ideas and not its “packaging” should make the difference. Ultimately, you win a case based on content. This content being eloquent is the cherry on the cake.

Bypassers often say: “Shouldn’t that work of art be switched on?” People who view the work have become so conditioned over time that they tend to think of neon lights when they see Not Necessarily Words. Maitre responds to this. He wants to shape our collective subconscious mind and to use the intellectual baggage we have gained from years of being “fed” with neon art by Maitre’s famous colleagues.

These artists’ first experiments date back to the 1940s, but neon only really took off in the 1960s and 1970s with artists such as Joseph Kosuth, Bruce Nauman and Mario Merz. They created neons that were then displayed in museums. After that, those images were used in the media, either literally or as derivatives in the form of neon advertising slogans. Their artworks are therefore engraved in our collective subconscious. That is why we have an immediate and somewhat silly response to a simple piece of ceramic, wondering if it can’t be switched on. In this way, the words Not Necessarily Words can also be read as follows: it is about the difference between what it says and what can be read. You’re looking at words, but these are also a representation of our collective memory, full of images and experiences.

There is a strong tendency to take everything put in front of us for granted or even to consider it to be true. We take one look at Not Necessarily Words and we see a text instead of a designed work of art. The sentence itself dominates our thoughts and the form has become subordinate to the words. Through Not Necessarily Words, the artist confronts us with our ingrained viewing and thinking patterns.

Jean-Baptiste Maitre (b. 1978)

Shaped Cinema

Inspired by the art-historical term shaped canvas, Jean-Baptiste Maitre created a series of works of art (a book, photos and a film) in 2010, under the title Shaped Cinema.

The basic concept that a canvas or panel is rectangular, square or, in rare instances, round, was denied and contested by a group of painters who would become known as the shaped canvas artists. From the 1930s onwards, artists experimented with forms that deviated from these traditional basic forms as an expression of artistic freedom, of non-conformism, or, for example, to give the painted composition more three-dimensionality by adjusting the contours of the canvas. The shaped canvas took off in the 1960s with artists such as Richard Tuttle, Elsworth Kelly and Frank Stella. They wanted to be free of “behind-the-frame-illusionism”. In other words, they aimed to get rid of the mysticism that is supposedly contained in the rectangular paintings by Rothko, Pollock and other so-called Abstract Expressionists. They contested the idea that spiritual and intellectual paintings required set frameworks. The new generation of artists was looking for their own form of freedom, or in their own words, a new representation of truth. It brought about works that border on pictorial and sculptural art.

Maitre’s starting point for his film Shaped Cinema is a 1970s catalogue from the New York Museum of Modern Art. From the catalogue, he scans and copies paintings by Frank Stella as well as write-ups about them. He then cuts them digitally and edits them as you would with 35mm film rolls, including the perforations, next to each other. We now see the Stella catalogue reappear in photos, but fragmented and larger. Here, the Frenchman Maitre works as a Deconstructivist, a term coined by Maitre’s fellow countryman and philosopher Jacques Derrida. The paintings of the most progressive geometric shaped canvas artist of his time, Frank Stella, are “deconstructed” into strips and then rebuilt into a new work of art.

For the film Shaped Cinema, Maitre continues down this path: he digitally assembles the contact prints of the aforementioned photos into film. The urge for innovation and originality of the shaped canvas artists resonates with Maitre and, like his predecessors, he puts it into practice. But where shaped canvas artists add a visible third dimension, and thus sculpturally, to a traditionally flat and rectangular painting, he adds the factor of time by turning it into a moving image. Oddly enough, the film evokes an overall feeling of the 1960s and 1970s, partly due to the fragmentary, flickering effects. It is a digital film, made with the PC, but with an unmistakably nostalgic, analogue appearance.

It is a period that resonates with Maitre, which is also evident in another piece by him in the A&O Shearman collection: the ceramic work titled Not Necessarily Words, in which he again refers to the (neon) artists of the 1960s and 1970s. Here, too, he strips neon of all its original properties and builds up to something new that clearly refers to, but isn’t, neon. His deconstructivist approach gains Maitre new insights and new art.