Navid Nuur (b. 1976)

Broken Circle

Almost immediately after completing his education at the Piet Zwart Institute (he was politely rejected by the Rijksakademie (State Academy of Fine Arts) in Amsterdam), the Dutch art scene dubbed Navid Nuur a child prodigy, capable of just about anything. With an almost inexhaustible supply of ideas, put into practice in an equally broad array of disciplines and materials, he manages to present interesting work time and time again. The pieces are often based on a simple but well-thought-out concept. These concepts are surprisingly well executed and implemented. At an early stage, museums and other entities as well as collectors queued up to acquire Nuur’s work. At the 2019 Venice Biennale, one of the most prestigious art exhibitions in the world, his work was prominently displayed both in the city and on the Biennale grounds. It all turned out very well for Nuur. For it matters greatly to him who buys his work and where it is displayed, which is typical of the artist’s unbridled ambition.

Since 2006, Nuur has been working with neon on a regular basis. Disconnecting the lamps from their original context made him realise that at a certain point the lamps no longer functioned as a light source. Rather, they could be regarded as independent, luminous objects. With the removal of the functionality, a variety of purposes came to life. Initially, this resulted in disconnected letters or large bundles of tubes that are placed in the (top) corner of a room, not unlike a Mikado set, with the electrical wires chaotically tangled and draped on the ground. Nuur had the work Broken Circle implemented by a company who specialised in neon lighting. They were the ones who installed it onsite in the Apollo House. Broken Circle, as the title implies, is an imperfect neon circle. About a sixth of it is missing in the top left corner. However, the “unused” glass of the missing piece is very much present in the form of glass dust at the bottom of the hollow tube. The grit “irritates” the neon gas so that the light intensity is different in that particular spot. The result is a work that refers to cheap illuminated advertisements and evokes associations with the well-known Minimal artist Dan Flavin, who has been making sculptures from (coloured) neon and fluorescent tubes since the 1960s.

The combination of Navid Nuur’s Broken Circle with Tommy Grace’s Ad Ex works phenomenally well, not least because both works are inspired by famous kindred spirits from the 1960s.

Navid Nuur (b. 1976)

The Tuners

In 1972, German artist and mystic Joseph Beuys wrote down the phrase “Everyone is an artist”. Somebody had undoubtedly thought or said it before, but it is Beuys who will forever be associated with the phrase. That same year, he refused to comply with a rule that stated that no additional students would be admitted to the academy in Düsseldorf, where he was teaching at the time. He invited the rejected students into his class and taught them on the grass next to the academy. Of course, not everyone is literally an artist, but artists don’t have a monopoly on the creation of beauty.

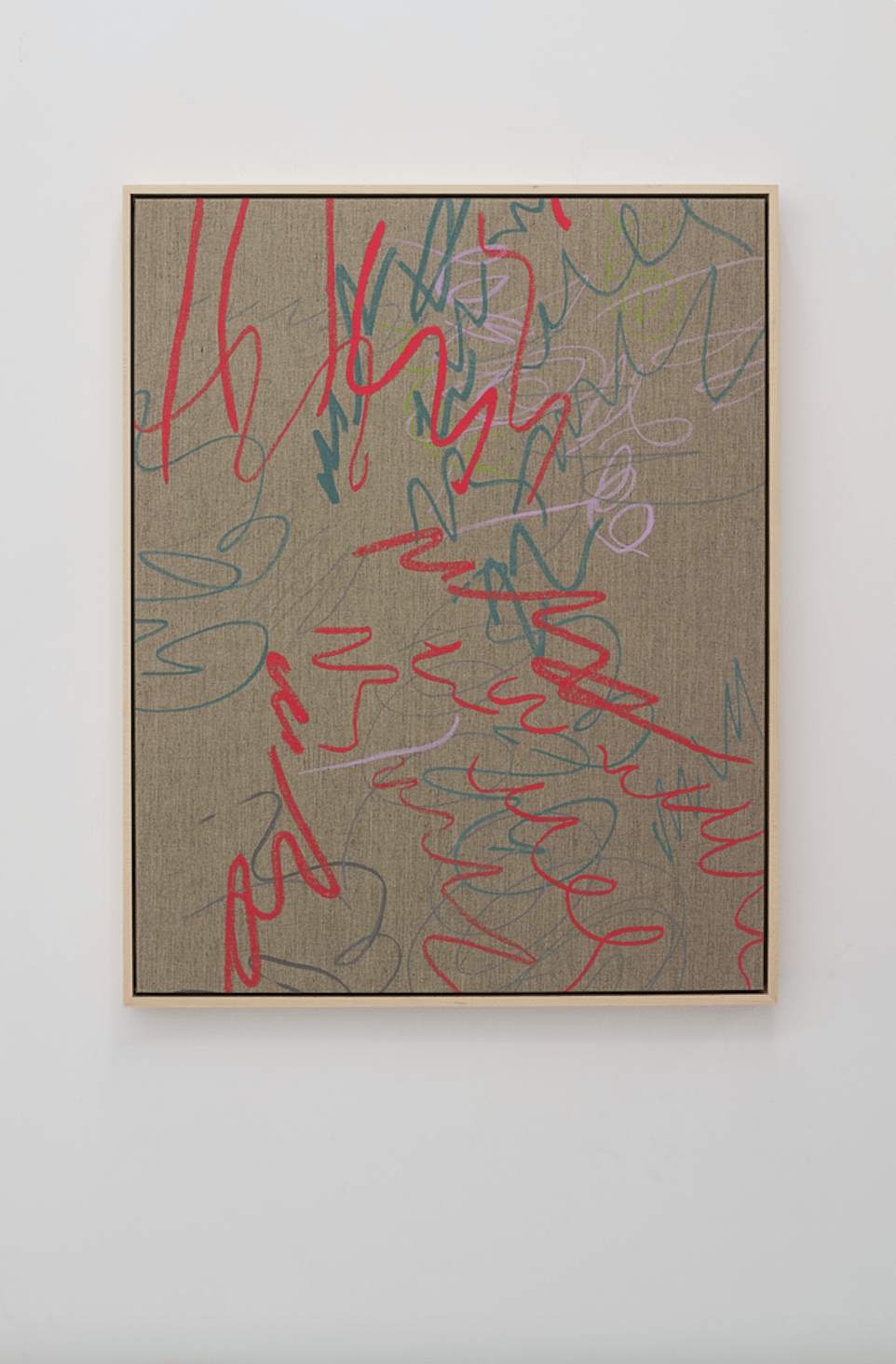

Navid Nuur can regularly be found in stationery stores and fountain pen boutiques, where he hunts for the notepads and school notebooks people use to test their new purchases, or in Nuur’s words: “tune them”. Large amounts of scribbles and doodles are copied minutely with paint onto a canvas. By making the handwriting of others his own and presenting it as art, Nuur keeps the spirit of Beuys alive. His appropriation of ordinary scribbles also touches on another important theme: authenticity. Because, who really created this work of art? Did we create this ourselves when we tested our new fineliner in the shop? If something may serve as evidence for the populist statement “My three-year-old son could have made this,” it may well be a painting from the Tuner series. But did the three-year-old also intend to place the scribbles so delicately on the canvas and to show them to the world as a work of art?

The “the three-year-old son” statement has probably been made most often in regard to the drip technique paintings by the American Abstract Expressionist Jackson Pollock. These famous paintings have had an enormous influence on our collective view on (abstract) art and on artists who came after Pollock. When viewing The Tuners, we are likely to be reminded of artists like Pollock. However, the starting points of Nuur and Pollock differ immensely. Pollock was dubbed the intuitive Action Painter, who created his works on the spot, dripping and splashing layer upon layer. Nuur, on the other hand, is forced to be extremely precise and careful when recreating someone else’s scribbled lines. The link between Nuur and the great pioneers of abstraction is nevertheless very apparent.

During the 2019 Venice Biennale, three enormous Tuners by Nuur were installed in the courtyard of the Conservatorio di Musica Benedetto Marcello. It was a beautiful sight, three large white paintings against a background of a 19th century urban palazzo. The term tuning took on extra meaning at that moment, as classical sounds from the music students could be heard coming from the open windows of the music academy. For a very brief moment, the scribbles seemed to function as musical notes.