Praneet Soi (b. 1971)

Bird

Praneet Soi is an Indian artist living in the Netherlands. Like many other young talents from abroad, he has come to the Netherlands to participate in a residency program at the Rijksakademie (State Academy of Fine Arts) in Amsterdam. He can often be found in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, studying the Old Masters. He studies their sense of detail and textural expression. He is also interested in 17th century ingenuity regarding perspective. He has an interest in the camera obscura, but also in anamorphic drawings that only come to life when viewed through a cylindrical mirror. It’s not necessary to look at Bird through such a mirror, but Soi does trick the eye in a surrealistic way. His limb placement is far from perfect and the proportions of body parts are difficult to gauge.

Besides the Old Masters, media images and newspaper photos are of great importance to Praneet Soi. He likes to “cut and paste” photos from newspapers to then transform the original, often iconic, footage into his own visual language. His choice of subjects is very personal and socially engaged. Looking at Bird, it’s hard not to think about the famous images taken in the Abu Ghraib prison, which were broadcast all over the world. It’s where Iraqi insurgents were humiliated and tortured by American soldiers, the so-called rescuers who came to bring democracy. Many artists across the globe have used the images to express their feelings of anger and impotence in their work.

Soi transforms the original image of the prisoner standing on a platform with something covering his head and electric wires attached to his hands, to create a softer, more subtle reference to the atrocities, without directing the viewer away from the association with Abu Ghraib. The iconic arms in the original photo are spread out, a universal symbol of powerlessness. Now, one hand seems to almost come out of the subject’s head, like a beggar’s hand. Together, the hands refer to the countless hands that have been pictured in universal religious iconography over the centuries. The spectrum goes from forgiving and healing hands to an exalted, Divine hand.

Studying Dutch cloth, for example in the honorary wing of the Rijksmuseum, pays off. The moth-eaten, gritty Abu Ghraib rug has been replaced by Praneet Soi with a God-worthy, meticulously painted, precious fabric. Where the Iraqi prisoner’s humiliating situation is further enhanced by the filthy blanket, the silk fabric protects the depicted figure in Soi’s painting. Here, anonymity does not lead to dehumanisation, rather to the exaltation above the imperfect, failing humankind. Seen in this light, the title Bird could refer to the Dove, a Christian symbol of reconciliation and peace.

Praneet Soi (b. 1971)

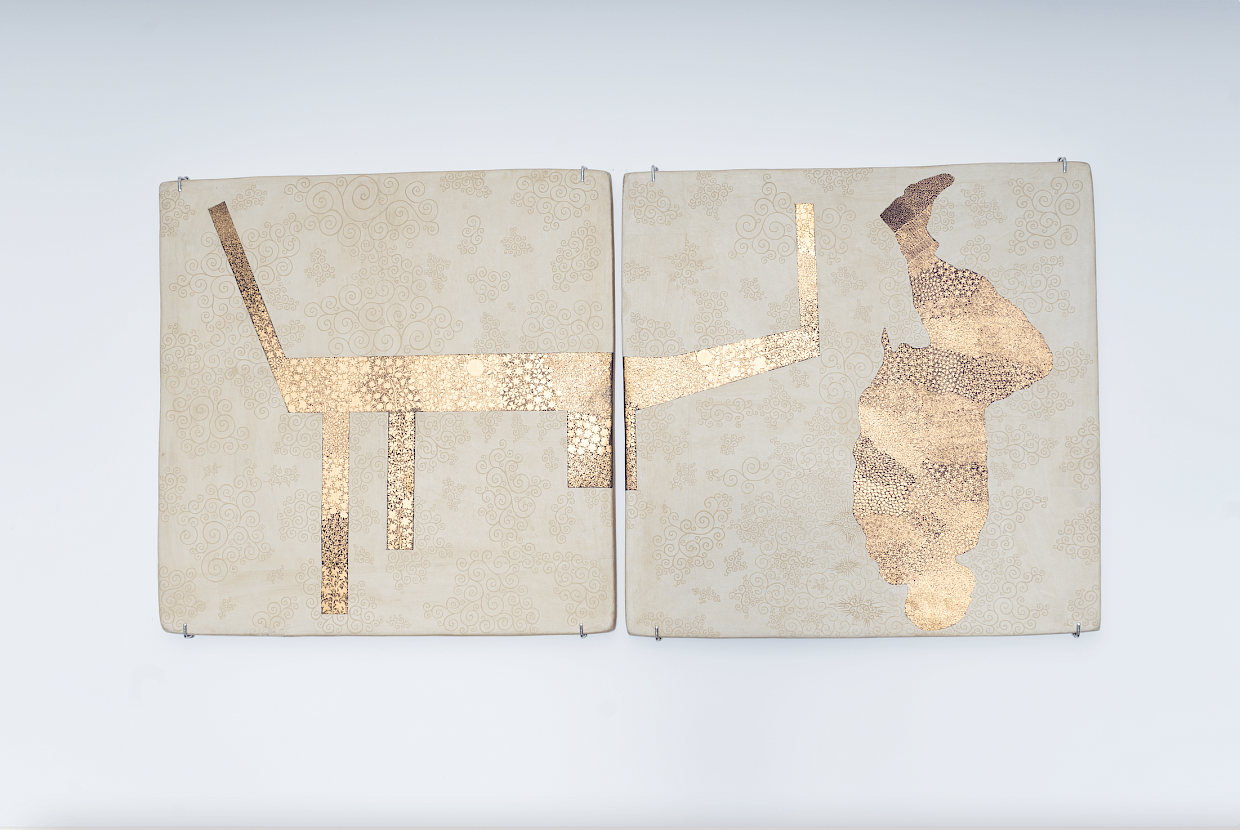

Falling Figures

The right half of Praneet Soi’s diptych Falling Figures is dominated by a familiar image that has been stuck in our collective memory since 11 September, 2001. It is the falling man who preferred jumping into the unknown over being burned to death in the Twin Towers. The image comes from an enormous archive of illustrations, mainly from the media, collected by Praneet Soi. On the left, we see an icon representing a falling man, or at least an artistic version of it. This turns the September-11-figure into a symbol for a nightmare scenario. Or maybe the fact that it has been marginalised into a picture, makes it easier for the viewer to deal with the heavy nature of what’s going on.

The background motifs and decorations were painted by Muslim artisans from Kashmir, India’s northernmost state, which has been fighting for independence since 1947. From 1989 onwards, the struggle for independence became a grim, armed dispute and it remains unsettled to this day. Bordering Pakistan, India’s nemesis, Kashmir is constantly claimed and disputed by many different groups.

Praneet Soi visited the area in 2009, out of curiosity about this part of his country that is constantly threatened by political and economic unrest. During his trip, he met Kashmiri artisans who make papier-mâché vases and bowls and decorate them with traditional patterns. Using his own archive of images, Soi started searching for the origin of the Kashmiri patterns and figures to find out that these originated in Persia, some 3000 kilometres away. The motifs are believed to have been brought to Kashmir by travelling Sufi priests as early as the 14th century. In 1372, Islam was spread by Shah Hamden in the then predominantly Buddhist Kashmir. In addition to the new faith, he also introduced the technique of papier-mâché for the artisans to start a new “industry” and thus to boost their self-esteem. The Kashmiri arts and crafts industry, therefore, owes its existence to centuries of migration and Praneet Soi makes grateful use of that tradition to elaborately validate the democratizing effect of art.